- Home

- Paul Hazel

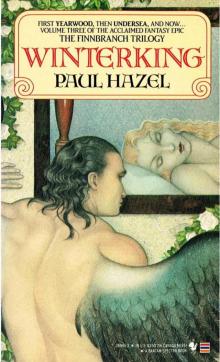

Winterking (1987)

Winterking (1987) Read online

FIRST YEARW OOD, THEN U N D ERSEA , AND NOW ...

VOLUME THREE OF THE ACCLAIMED FANTASY EPIC

THE FINNBRANCH TRILOGY

WINTC1RKING

PAUL HHZ6L

2 6 9 4 5 3 * IN U S S3/5l)'(IN C A N AD A $ 4 9 5 )

,

_ # A 8 A N TA M .SP E C TR A BOOK

TH E

FINNBRANCH TRILO G Y

_______ BY PAUL HAZEL

VOI.UHL ONE:

YGflRWOOI)

“ One of the best

high fantasies in some time.”

-

—Publishers Weekly

5S

“A dark, strikingly original book.”

E-

-IVterS. Beagle

2T

“ In the spirit

b

of Tolkien and C.S. Lewis.”

h5

I he Siientmcnlo Btr

-E

VOLUML TW O :

<<<br />

UND6RS6A

ES

“ The reader is accorded glimpses

Q

of an enchanted world, a world of

shore and sea, not ours,

and yet echoing in the mind like

something long ago lost and

forever missed."

Ku.ierl Mi Kinley,

author ol the Hie Ilero ,ind the ( rown

“DEAR CALLAGHAN”

He folded the single page over and set it aside.

He had killed before, both with his own hands and by

proxy. He had never pretended, as men often did, that both

cases were not very much the same, but he had been at it

longer and had less reason to lie to himself. The wars in

which he had taken his first heads and left the bubbling necks

empty were no longer remembered; the lands over which he

had fought were no longer lands, but ocean. Yet he had never

failed to understand what it meant or what a powerful thing it

was to take a life or to be less frightened by it.

He did not expect to be understood. He knew that not

even the most rugged men now living could have lived as he

had lived, gone where he had gone, or done what, to the

horror of his soul, he had had to do.

1 must ca ll you again into service, he wrote at last.

H ousem an, fa ilin g , is d ea d a n d I sh all trust no on e else in this

en terp rise. I have no o th er rew ard to o ffe r you except my

affection ; he stopped, then added, everlastingly.

Beneath the tiny printed letters he set a large cursive “W"

Bantam Spectra books also by Paul Hazel

Y EA R W O O D

U N D ER SE A

(Volumes 1 and II of T he Finnbranch)

WINTERKING

Volume III of The Finnhranch

Paul Hazel

BANTAM BOOKS

TORONTO • NEW YORK • LONDON • SYDNEY • AUCKLAND

This low-priced Bantam Book

has been completely reset in a type fa ce

designed fo r easy reading, and was printed

from new plates. It contains the complete

text o f the original hard-cover edition.

NOT ONE WORD HAS BEEN OMITTED.

W IN T ER IN G

A Bantam Spectra Book / published by arrangement with

Atlantic Monthly Press

PRINTING HISTORY

Atlantic Monthly Press edition published October 1985

Bantam Spectra edition / December 1987

All rights reserved.

Copyright © 1985 by Paul Hazel.

C over art copyright © 1987 by Mel Odom.

Library o f Congress Catalog C ard Number: 85-47786

This book may not be reproduced in whole o r in part, by

m im eograph or any other means, toithout permission.

For information address: Atlantic Monthly Press,

8 Arlington Street, Boston MA 02116

ISBN 0-553-26945-3

Published simultaneously in the United States and Canada

Bantam Books are published by Bantam Books, Inc. Its trademark, consisting o f the words ”Bantam Books" and the portrayal o f a rooster.; is Registered in U.S. Patent and Trademark Office and in other countries. Marca Registrada. Bantam

Books, Inc., 666 Fifth Avenue, New York, New York 10103.

P R I N T E D I N T H E U N I T E D S T A T E S O F A M E R I C A

o

0 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Natalie Greenberg

Ah, it’s a long stage, and no inn in sight,

and night coming and the body cold.

— Herman Melville

in a letter to Nathaniel Nawthorne

I .

The River

1

.

The photographs of that time, printed from glass plate

negatives, reveal a landscape at once more barren and

roomy, a world puzzlingly larger (not merely less cluttered)

than the world bequeathed to 11s. The pastures to either side

of the Housetenuc, the sixty river miles between Devon and

New Awanux, had then only lately begun to close again with

trees. But the trees are small, all second growth; the men do

not as yet seem uncomfortable beside them. Their expressions reflect no amazement at the huge bald earth nor any knowledge of their little place in it. Their reputation for being

perceptive, while not entirely undeserved, did not truly

encompass the land. To them it was Eden though the fires of

workshops and mills made a twilight by midday over the

rutted hills. The lie which their fathers had carried across the

Atlantic persisted with the sons. But the land had never been

Eden, 'not even when a wilderness of gloomy wood had

covered the valley. The last naked men living along the upper

reaches where the river was narrow and stands of sycamore

still crowded out the sun knew all the while it was Hobbamocko,

not Jehovah, who ruled there. The English, however, who

had covered their genitals far longer than they had been a

nation or gone over the sea, never asked them.

So it happened that Jehovah’s white clapboard houses,

like a species of mechanical mushroom, sprang up inexhaustibly.

There were four on the Stratford flats. In New Awanux itself

there were twenty. Old Qkanuck, son of Ansantawae, the

wind of memory blowing across his mind, sat laughing merrily in the corner of the longhouse and struck his hams. Alone, he had burned seven of Jehovah’s houses, had walked up to

them boldly across the green commons, bearing a torch in

3

4

WINTERKING

each hand. The ghosts of those burnings still flamed in his

eyes. The warriors saw it and were cheered.

“The land did not want them,” old Okanuck said. “If it

had, those houses would have grown back, like the madarch,

drawing their substance from the bones of the buried wood.

So our longhouses grew then, year after year in the same

place, nested in the damp, in the oak-shade, taking their

strength from the ground.”

A smile sank in his toothless mouth. Like the earth he

had darkness inside of him. And foxcubs and black birds, he

maintained, shaking with laughter. And a thousand oak trees,

windstorms and the seeds of spiders. �

�Only see that I am

planted deep,” he howled gleefully, "and I will grow a world

again. A better world.” Old Okanuck winked. “No Awanux.”

They gave him his pipe.

When the silence had lasted for many heartbeats, a boy

with thunderous brows reached across to touch the old one’s

shoulder. The faces of the men turned on him disapprovingly.

But Okanuck, setting the pipe aside, gave him an encouraging nod.

“The Awanux are many,” the boy said angrily.

Okanuck did not take the boy any less seriously but

grinned. “We are more,” he said kindly. With a sweep of his

outsi/.ed hands he motioned the boy to sit nearer and to share

the pipe. Okanuck watched as the boy parted his lips and

sucked in great quantities of maggoty smoke. But, though the

smoke filled the boy’s chest, inside there was emptiness. The

smoke was drawn in and lost.

“O nce,” the boy said, uncomforted. “Perhaps it was

different then. But now it is they who increase.”

Okanuck leaned forward. “They are only a frost,” he said

slyly, “a frost on Cupheag, on Metichanwon, a chilly smear

on Ohomowauke. . . .” His brows were lifted. Despite his age

his hair was black as oak-shade. “Who, knowing the frost,” he

asked, “fears it?”

Outside the longhouse the valley was sealed by cloud.

Okanuck felt no resentment. He laughed.

“The earth is under it,” Okanuck said. “Deep down.

Undying.” Gingerly, with the clawed edge of his toes, he dug

for lice, scratching in the mat of dense feathers on the

underside of his black and cobalt wings.

The River

5

“Crows?”

“Surely not,” was the immediate answer. “Dark, nameless

birds. The type doesn’t matter. But water birds of some sort,

I should think— though, of course, the shapes are drawn from

the earth, not the river.” He smiled. “. . . Pulled aloft from

the fields and then transformed, one pattern to the next, until

they soar.” Turning in his desk chair, the speaker pointed.

“The white birds, on the other hand, emerge directly from

the sky ”

He paused, appearing to search for a phrase which, in

fact, he knew quite precisely. “As though,” he began again,

“some quality in the white horizon. . . in the whiteness

itself. . . exactly matches the whiteness of the birds.” He let

that sink in. “See, near the top— to the left of the center

line— how the birds begin all at once, sky and birds in one

tessellation— simultaneously. You do see it?”

The younger man nodded but continued to examine the

woodcut of white and black birds silently.

Pleased with his explanation, the speaker went on smiling. He was perhaps a decade older than the younger man, just a shade past thirty and already balding. The woodcut

hung on the south wall of the study. It had taken him the

better part of six months to save for the print. Now as his

gaze traveled appreciatively over the repeated images of

birds, his sense of uneasiness in the younger man grew a bit

sharper. Yet for another moment he chose to ignore it. He

tipped a little farther back in his chair.

His name was George Harwood. He was an assistant

professor of Awanux. He had a blonde wife and a five-year-

old daughter, neither of whom he could quite afford. He lived

with both in three cramped rooms in the basement of West

Bridge Hall, where individual scholars before him had lived

since the time of its founding. His duties, for which he was

paid only slightly more than the wage of an instructor,

included tutoring a dozen or so of the more promising young

men. And this young man, with his long, odd, unboyish face,

was accounted to be the most promising.

Indeed, Harwood had long since been aware of a twinge

of jealousy whenever he considered Will Wykeham. Harwood

himself had once been thought of as something of a prodigy, a

man to be watched. This was not boasting. When he was

barely nineteen he had produced a thousand-page study of

6

W1NTERKING

the myths of the Flying Dutchman, a study of such scope and

interest that, he had been assured, with a very little tightening

it might well have found a berth at the college press. But

there had been interruptions. He had been burdened with

other matters and the work had dragged on without completion.

Wykeham, of course, had yet to accomplish anything of

equal breadth or learning, a paper on Chaucer, a few brief

articles on Milton, jewel-like, it was said, nearly perfect but

on a small scale. The younger man had a talent for appearing

to inhabit the author’s world, an instinct for the nuances of

language now fallen out of use, an instinct which permitted

him to suggest a number of rather clever interpretations,

wonderfully clear once he mentioned them but previously

escaping the attention of more seasoned scholars. The senior

faculty noticed him. On one occasion hearing Wykeham

deliver a paper on Paradise L ost the Dean himself had

whispered discreetly to Harwood, “One might well suppose

the boy had lived in the Garden and had spoken personally

with the Snake.” Harwood’s mouth had twitched up at the

corners. The Dean, who was a kindly man and inclined to

like undergraduates indiscriminately, promptly forgot the remark. It was envy that caused Harwood to remember it nearly half a year until at Greenchurch, on the edge of panic,

the words came back to him.

Beyond the window the river was blurred with cloud.

Having turned away from the woodcut, Harwood found

the younger man looking at him intently. For an instant

Harwood had the curious feeling he was staring directly into

the blank March weather. The eyes, while not large, conveyed

an almost overwhelming bleakness, as though through their

slight openings Harwood glimpsed the cold mist and the hills

beyond them, fading north in the rain. But it was the long

square face that had most shaken him. The strong features,

gathered close to the center, left an expanse of unexpected

whiteness. It was a face with room in it. Whatever trouble

had momentarily set its mark there, the face itself, with a

surprising sense of quiet, remained essentially free of concern. Harwood found himself suddenly ill at ease.

“You said they reminded you of crows,” he said unevenly.

“I’m sorry. Not really.” Wykeham’s voice came from

miles off. “I was just thinking of crows.” For a time the

younger man looked past him, staring through the window at

The River

7

a clump of elms set off at the edge of the broad college lawn.

"I saw one this morning. A great scrufly-looking fellow. Too

big for a shore crow. It was waiting for me by the post office

gate when I went for the mail.”

“Waiting?”

Wykeham’s frown vanished. “I think so,” he said. His

eyes turned abruptly toward Harwood. “You might say a

&nbs

p; prophet of doom.” Wykeham reached across his chest and

into the inner pocket of his jacket and drew forth an envelope. He dropped it on the desk in front of Harwood.

“You may read it,” Wykeham said. “But the short of it is,

I shall be leaving New Awanux by Saturday.”

With one pink hand Harwood reached halfway to the

letter. Both men shared a love of light holiday literature.

Harwood lifted an eyebrow, “Oughtn’t you have said,” he

bantered, “ I must be gone before morning’?”

Wykeham managed to smile and sigh all at once. “Really,

George, this is serious. You might at least have a look.”

The envelope was addressed: William Wykeham, Esq.,

College Station, New Awanux-on-Housetenuc. The address,

set down in yellowish-brown ink, was large and florid, with

much embellishment and too many capitals. Harwood glanced

at it dubiously before pulling out four sheets of white paper.

He laid the letter on the desk in front of him and began to

read.

“My Dear Mr. Wykeham, Undoubtedly the lawyers have

informed you of the untimely demise of Michael Morag.

Clearly your guardian was a just man and died peacefully (as

his service deserved), leaving your affairs in good order and

myself, as I believe those same lawyers must dutifully have

written you, to manage and discharge them in his place. I

regret I had not the pleasure of meeting him. Indeed he must

have been a most pleasant man as is well evidenced by the

comforts of the parsonage wherein for so many years he

resided, where I (by terms and covenants of the Will and by

my appointment lately to this parish) consider myself now

fortunate to have established my own household.

“I am told that yourself you never met the Reverend Mr.

Morag, although it cannot be more, at least not greatly more

(if it is not too discourteous to remind you), than sixty miles

from New Awanux to your properties here in Devon, and th e

trains run w ith some frequency! But then, of course, you have

8

WINTERKING

been traveling and had only come to these shores, as it were,

and at that for the first time, when you matriculated and have

Winterking (1987)

Winterking (1987)